Encouraging Creative Insight

When Inspiration Strikes

Do you remember what it felt like the last time you experienced a lightbulb moment? When a revelation hit you out of nowhere? These instances of sudden comprehension, called creative insights, are experienced across areas like perception, memory retrieval, language comprehension, and problem-solving. It’s these spontaneous occurrences of valuable new ideas that contribute to breakthroughs in innovation and artistic expression across every field – from science and technology to humor, entrepreneurship, and cooking.

Given its pervasive role in helping us solve problems and push boundaries, it’s natural to wonder: can we become more creative? Let’s dive into the brain science of these ‘aha’ moments, exploring how creativity works and what we can do to encourage it.

The Phases of Creative Insight

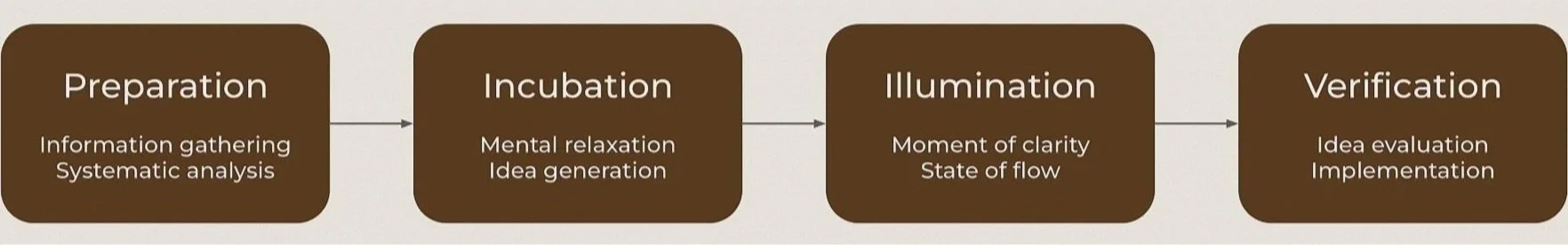

The most influential theory of creative thinking traces back to 1908, when mathematician Henri Poincaré identified distinct phases of creativity and underscored the critical role of unconscious incubation of ideas. Psychologist Graham Wallas further developed the theory in his book, The Art of Thought (1926), which continues to be widely cited today. He distinguishes between four phases of creative thinking: preparation, incubation, illumination, and verification.

The preparation phase is about framing the problem and methodically analyzing it from all angles. Then comes incubation, where the unconscious mind takes over, processing the problem in the background. The illumination phase kicks in as a solution or idea surfaces toward consciousness – this is the flash of insight we experience. Finally, the verification stage includes assessing how useful the idea is and whether it needs further refining.

While these phases have been represented above in a linear fashion, the reality of creative work is messier. They aren’t necessarily discrete steps that come one after the other in a tidy sequence. You may come up with numerous ideas over time, keeping some and discarding others in multiple rounds of trial-and-error. You incubate new ideas for one problem while you’re busy implementing your ideas for another. Your moments of illumination and verification trigger further generative processes that send you cycling through these operations many times over.

Preparation

The preparation stage is all about structuring the problem, gathering information, and systematically generating ideas. We have to prime the mind for creativity with directed conscious work. We examine the problem from multiple perspectives and brainstorm potential solutions or ideas, using our imaginations and structured thinking. A free-rein approach that embraces playfulness is key here, as it’s crucial to generating lots of random ideas – this is why we say “there are no bad ideas” during brainstorm sessions.

During this stage, when our attention is narrowly focused, the left hemisphere of the brain does the heavy lifting – it runs the show when it comes to consciously directed analytical analysis.

Incubation

As the amount of information processed increases and the problem remains unsolved, we may experience a widening of our attention or a loss of focus. We might take a break from problem-solving. Once we are no longer consciously focused on tackling the problem, we enter the incubation stage, where our unconscious minds continue to work in the background, combining ideas in novel ways. It is this kind of processing that distinguishes creative insight from non-creative.

During incubation, increased activity appears in the default mode network, a network of regions in the brain that is less active when we are focused on external tasks and more active during internally focused thought processes like daydreaming or meditation. It’s the brain’s “default” pattern of thought when we’re not focused on some specific mental task and it allows connections between seemingly unrelated ideas.

Illumination

Once our brain has made a promising connection – typically while we are engaged with something else entirely – we are suddenly struck with a flash of insight. We consciously experience the emergence of a new idea. Eureka! The lightbulb has turned on and the illumination phase has begun.

In the brain, just before the answer erupts into consciousness, the anterior superior temporal gyrus (aSTG) lights up with gamma waves, which indicates the formation of novel remote associations.

Verification

Throughout the course of a complex creative project, you may have countless ideas and insights. Verification is the phase where ideas are evaluated, with only a few of them making the final cut. For any idea that occurs to you, you might have to ask: Will this work? Is it new? How does it fit in with other parts of the project? Do I have the resources and abilities to bring it to fruition? Is it worth the time and effort?

Fostering Creativity

The story of how Milton Glaser created the iconic I ♥ NY logo shows the creative process in action. Glaser, a graphic design legend, has created many iconic illustrations, from the 1967 Bob Dylan silhouette poster to the DC Comics logo to a staggering number of product labels sitting on supermarket shelves. His images have entered the permanent collections of MOMA, the Smithsonian, and the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum.

In 1975, he was asked to create an ad campaign that would rehabilitate the image of New York City, at a time when Manhattan was falling apart and the city was almost bankrupt. “When people thought about the city, they thought about dirt and danger,” Glaser recalls. “And they wanted a little ad campaign that could somehow change all that.” He was given one additional constraint: the print ad had to use the phrase, “I love New York.”

After a few weeks of experimenting with various fonts and layouts, he settled on a charming cursive design, with “I Love NY” set against a plain white background. He submitted his proposal and it was approved, but he continued to fixate on the design, spending hours thinking about it. “I can’t get the damn problem out of my head,” he says. “And then about a week after the first concept was approved, I’m sitting in a cab, stuck in traffic. I often carry spare pieces of paper in my pocket, and so I get the paper out and I start to draw. And I’m thinking and drawing and then I get it. I see the whole design in my head. I see the typewriter typeface and the big round red heart smack-dab in the middle. I know that this is how it should go.”

The graphic that he imagined in rush-hour traffic has become the most widely imitated work of graphic art in the world. Because he refused to stop thinking about the three-word slogan and kept redrawing the logo in his mind, his ideas continued to improve. “I could tell you a bullshit story about what exactly led to the idea [of I ♥ NY], but the truth is that I don’t know. Maybe I saw a red heart out of the corner of my eye? Maybe I heard the word? But that’s the way it always works. You keep on trying to fix it, to make the design a little bit more interesting, a little bit better. And then, if you’re really stubborn and persistent and lucky, you eventually get there.”

Reflecting on this story and relating it to the phases of creative thinking sheds some light on what’s happening in the brain when we tackle problems and tells us how we can encourage creativity. When faced with a problem, we first take an analytical approach, primarily engaging the left hemisphere of the brain to systematically think through potential solutions. Eventually, after we hit a wall, that feeling of frustration sets in and we start to lose focus – maybe we start daydreaming or decide to take a break. At this point, brain activity shifts to the right hemisphere, marked by alpha waves emanating from this region.

The right side of the brain is the creative powerhouse. It finds subtle connections between seemingly unrelated things – without it, we wouldn’t understand jokes, sarcasm, or metaphors. The right hemisphere enables us to see the whole in addition to the parts – to see not just the trees, but also the forest. It’s the creative machine that works in the background, hidden from our conscious awareness as it sorts through abstract concepts, connecting them to other concepts, items, events, or experiences. Once a valuable connection is found, the anterior superior temporal gyrus (aSTG) – where integration of conceptual knowledge happens – lights up with gamma waves. The brain has generated an insight that erupts into consciousness – the lightbulb turns on.

Balancing Focused Work and Relaxation

The cornerstone of the entire process is unconscious incubation and its corresponding alpha waves, which are associated with a relaxed state of mind and a lack of directed conscious thought. Alpha waves are thought to be a mechanism used in the brain to inhibit our habitual thought patterns; they create the space for ‘out-of-the-box’ thinking. In fact, stimulating the right temporal lobe with an electric current that mimics alpha waves has been shown to improve divergent thinking. This means we can increase the likelihood of creative insight by engaging in relaxing activities where your attention is not focused outward – yoga, meditation, daydreaming, aerobic exercise, and even warm showers are all associated with an increase in alpha waves.

But relaxation by itself isn’t enough – you also have to exercise the persistence and good judgment demonstrated by Glaser when he produced the I ♥ NY graphic. You must pay attention to the ideas and connections your brain is forming and keep them in your working memory. And since insights come from the overlap of seemingly unrelated thoughts or ideas, you have to keep thinking about the problem and possible solutions – this gives your unconscious mind raw material to work with. The trick is knowing when to grab coffee and push forward vs when to take a break.

Learning how to quiet your inhibitions, similar to how a jazz player might while improvising, will also help creativity flow freely. Engaging in activities that invoke the flow state, like exercise or art are particularly helpful, as are mindfulness and meditation, which foster relaxation that encourages associative thinking. Maintaining a ‘beginner’s mind’ – viewing challenges with fresh eyes – is also important. Stepping away from a problem and returning much later can help you regain this perspective. Exposing yourself to new ideas and people, traveling to new locations, and looking for new challenges are all good ways to stimulate creativity. You have to cultivate an open mind and seek out sources of new perspectives.

Interestingly, psychedelics can also improve out-of-the-box thinking by inhibiting our habitual thought patterns. By activating particular serotonin receptors (5-HT2A) in the brain, psychedelics promote excitability of neurons and increase disorder in the brain, effectively reducing the filtering of information that reaches conscious awareness. This shift reduces the brain’s tendency to form perceptions based on past experience, making it easier to override ingrained beliefs and form new ideas.

Creating Space for Creative Insight

Creativity is often viewed as a mysterious gift, reserved for the inspired few, but we now know it’s a skill that can be somewhat cultivated and encouraged. By understanding the phases of creative thinking, and the relationship between preparation and incubation in particular, we can better equip ourselves to have more of those elusive lightbulb moments.

Whether it’s structuring a problem and gathering information carefully, letting ideas simmer through downtime, or learning to recognize and capture insights surfacing from the unconscious, creativity thrives on a balance between focus and relaxation. By taking breaks and engaging in mindful activities in between bouts of focused work, we create fertile ground for creative insights to emerge.

In the end, creativity isn’t just about the big breakthroughs; it’s about cultivating an open mind, a willingness to explore, and the patience to let ideas develop in their own time. So, next time you’re working through a problem, try giving your mind the space it needs to make unexpected connections. You never know when inspiration might strike.

References

Ananthaswamy, A. (2021, July 7). Psychedelics open a new window on the mechanisms of perception. Nautilus. https://nautil.us/issue/102/hidden-truths/psychedelics-open-a-new-window-on-the-mechanisms-of-perception

Carhart-Harris, R. L., & Friston, K. J. (2019). REBUS and the Anarchic Brain: Toward a unified model of the brain action of psychedelics. Pharmacological Reviews, 71(3), 316–344. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.118.017160

Creativity (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). (2023). https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/creativity

Gardner, H. (1993). Creating Minds: An Anatomy of Creativity Seen through the Lives of Freud, Einstein, Picasso, Stravinsky, Eliot, Graham, and Gandhi, New York: BasicBooks.

Jung-Beeman, M., Bowden, E. M., Haberman, J., Frymiare, J. L., Arambel-Liu, S., Greenblatt, R., Reber, P. J., & Kounios, J. (2004). Neural Activity When People Solve Verbal Problems with Insight. PLoS Biology, 2(4), e97. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0020097

Lehrer, Jonah. (2012). Imagine: How Creativity Works. Canongate Books.

Luft, C. D. B., Zioga, I., Thompson, N. M., Banissy, M. J., & Bhattacharya J. (2018). Right temporal alpha oscillations as a neural mechanism for inhibiting obvious associations. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1811465115

Sandoiu, A. (2018). How brain waves enable creative thinking. Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/323956

Shen, W., Yuan, Y., Liu, C., & Luo, J. (2017). The roles of the temporal lobe in creative insight: an integrated review. Thinking & Reasoning, 23(4), 321–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/13546783.2017.1308885

Wallas, G. (1926). The Art of Thought. London: J. Cape.

Waytz, A., & Mason, M. (2013). Your Brain at Work. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2013/07/your-brain-at-work